1,2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9

And yes, I suppose it is time to tell you that story, the one about the black currents. I assure you, dear reader, that it is a most true and touching one. A light touch, fair and sprightly enough to please even the worships of a Sterner era. But one with morals and models for our own moral-less age. For it is no longer politically correct to hide your morals within the confines of a fairy tale. Fairy marraiges are filled with too much controversy, but to stray upon these matters would take us too far from the point. Rather, you should merely lose your points and morals altogether, and then hide yourself to make sure that they do not find you.

But let's repair to the study and so I can tell my tale properly. Come in, shut the door behind you against the flies. Patrick tells me that I am only the third to write in this study. He knows all of the house history you see, all of the years of silence. Jonathan Coe was here last week, working away at a lecture he had to give that same night. He banged out six thousand words from 8 to 3 and all that while he was ill. The voices here are too strong for me, I cannot count my own words.

First, to tell my tale, I must switch on the light. I almost envy Sterne now, for all he had to do was catch a goose, pluck its feathers, carve a pen nib into its bone, distill some ink, wring out some rag paper, dip the pen, write the message, blot the paper, and go on. Go on, touch the feathers and marvel that his pen is from such simple technology while I make ready for today. Mind the gaps in the previous sentence, just as they tell you during that plunge. Of course, sometimes an underground is just an underground.

First I must find the power to write, then plug in my computer, my travelling companion. Come on, lend a hand. Help me find the plugs, the means I must have to tell you about the black current in this cosy ancient room. The plug and light switch are the only current things here, and ahh there, thank you Madame, for moving your long skirt, you have revealed them. They are hidden neatly, discretely located by the fire. The surge of the grid invades even this space, touches even the old tea roses swaying outside the window. There, reader, I am plugged in. And I may, on Sterne's behalf, invite you properly now into his study. He has had readers here before, you know, so this is no interruption, and we may as well all of us enjoy the day. A fine day outside, no haze, and clear. But we should shut the window, as all of the books here strain towards it and loose their bindings, the better to smell the day and let their meaning soar.

Too late, I am afraid. There goes half the tale out the window. Reader, I depend upon you to close that space before we lose everything. Reader, do your duty.

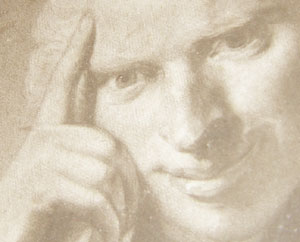

Sterne is sitting on the mantlepiece, his elbow cocked and index finger raised to cradle his head. His amused avuncular grin and wide eyes are barely held in place by this arrangement, and that grin is ready to float down off the wall and perch on the top of my laptop, a cheshire cat exploring other provinces. A mezzotint of the portrait by Sir Joshua Reynolds. This seems to be his only--or perhaps merely just his best likeness, and graces all the books as well as holding center sway in this small study.

"A vivid likeness

of Laurence Sterne still seems to fail the Georgian portrait gallery.

The frame is there, and the wan, pensive, roguish face, with the lips

maliciously sentimental. But the soul, about which Sterne declared himself

so 'positive,' the soul which contradicted his actions, is missing. He

has been much written about, mapped out, dissected, criticised, but maps

and anatomical plans are never portraits." begins Walter Sichel,

in his Sterne, A Study (London: Williams and Norgate, 14 Henrietta Street,

Covent Garden, W.C., 1910)

Ahh the theorists have been at the beast and have stripped it off its bones. And has anyone truly discovered a soul in a piece of paper? A print? A monitor? There, look up at the beams and tell me that you do not see Sterne's grin fading and refading amoung the rafters. ****** You see, you cannot do it. Well, then, as you are trapped in your brambles of double and triple negatives, just doff your hat and say hello to him. You can't get more scratched up about it than you already are. And his grin--when it is not flying about the room, may just peek out from the17th century Universal Dictionary (and Supplements), and smirk at you out from under the gaps in the bookcase. For he knows, as we all know, merely and just this:

We are all of us talking to the skulls that went before. Alas poor Yorick, I knew him well. Or ill. Or not at all. We are all of us looking out of our own skulls only, blind binders of bone. We cannot see from side to side, we cannot see what went before and what after. "Ten times in a day has Yorick's ghost the consolation to hear his monumental inscription read over with such varity of plaintive tones, as denote a general pity and esteem for him." Tristram is careful to assure us. Yet what truly reaches Yorick's dead and long decayed ears?

| Tristram Shandy ducked the whole affair, by following up his obsequies to Yorick in an ineffable black. There is nothing current in Shandy's black meanings. | We can no longer do the same, our black current spaces must needs have words, our black currents must run with the juices of a thousand thoughts, of the zooming past of motorcycles and horns. |